The Experiment

Early days: An idea takes shape

This story begins in 1969, with a zoologist named Robert T. Paine, who spent his days studying starfish and mussels in Pacific tidepools in the northwestern USA. Recognizing that starfish played a disproportionately important role in the structure and functioning of these tidepool ecosystems, Paine coined the term “keystone species” to describe them. Since then, keystone species have been identified in ecosystems around the world, including sharks on coral reefs, beavers in watersheds, wolves in forest ecosystems, and sea otters in kelp forests. The dynamics of keystone species populations have the capacity to shape entire ecosystems.

In 2012, a group of scientists posed the question: is there something like a keystone species in the seafood industry? To investigate this question, researchers at the Stockholm Resilience Centre (SRC) at Stockholm University, the Beijer Institute of Ecological Economics and the Global Economic Dynamics and the Biosphere program (GEDB) at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences began research on the largest actors in the seafood industry.

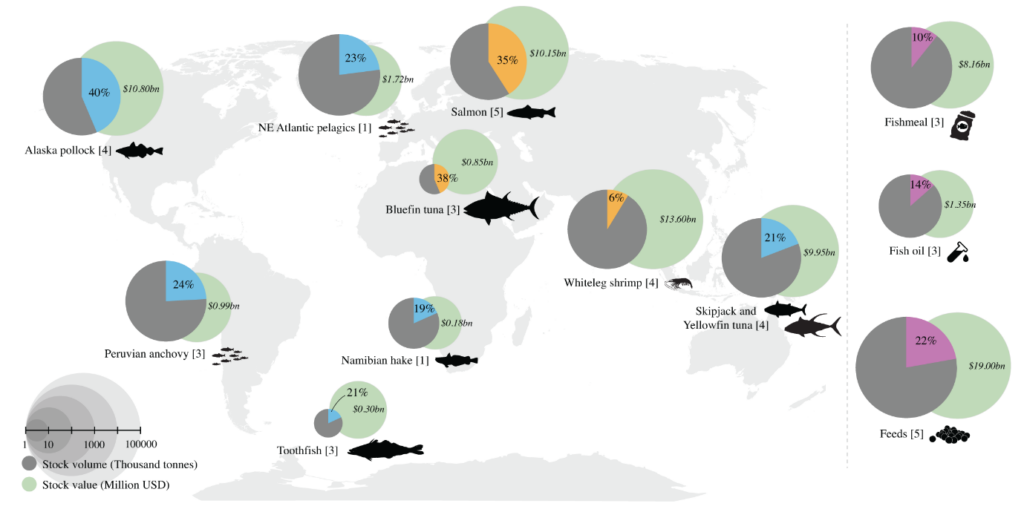

Their initial findings were published in 2015 in the paper Transnational Corporations as ‘Keystone Actors’ in Marine Ecosystems. They found that just 13 companies controlled 19-40% of some of the largest and most valuable stocks, and 11-16 % of the global marine catch. These “keystone actors” were defined as large corporations that:

- dominate global production revenues and volumes within a particular sector;

- control globally relevant segments of production;

- connect ecosystems globally through subsidiaries; and

- influence global governance processes and institutions.

The hypothesis

Inspired by the keystone species concept, the author group considered the seafood industry landscape they had described. What was the role of these keystone actors in the industry today? How were their actions shaping it? And what was their shared responsibility for the future of the ocean and sustainable seafood? The authors hypothesized that: “sustainable leadership by keystone actors could result in cascading effects throughout the entire seafood industry and enable a critical transition towards improved management of marine living resources and ecosystems.”

Collaboration emerges

Rich diversity exists within science, both in terms of how to gain knowledge and how to communicate and contribute this understanding to the world. “Sustainability science” has been described as a particular type of “use-inspired” research, aimed at translating knowledge into societal action: “its real test of success will be in implementing its knowledge to meet the great environment and development challenges of the century.”

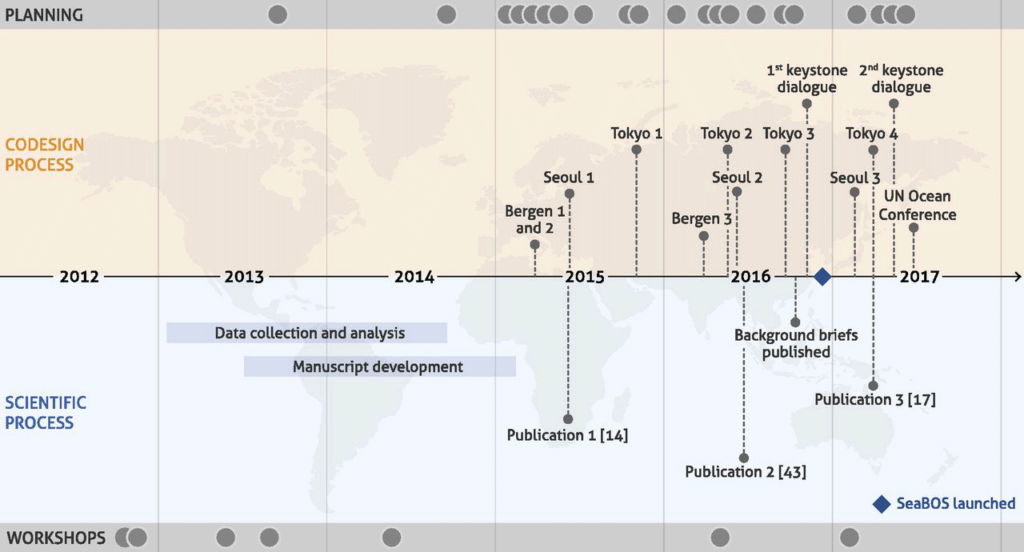

As sustainability scientists, the authors of the 2015 paper did not simply publish their findings and move on. Instead, they spent the next two years engaging with the 13 keystone companies identified by their research. They explained to the CEOs of these companies the concept of keystone actors and the disproportionate power enjoyed by this cohort of companies, as well as the scale of the challenges facing the ocean, in the form of fish stock depletion and collapse, climate change, pollution and more. And they asked the CEOs a simple question: “What challenges do you face today that you cannot overcome by yourself?”

In November 2016, eight of these companies agreed to meet for the first “Keystone Dialogue”. For the first time, CEOs of the world’s largest seafood companies gathered around a table together with leading scientists to understand their capacity, their role and their shared responsibility for ocean stewardship. The dialogue was elevated by the presence of HRH Crown Princess Victoria, who had taken on the role of advocate for Sustainable Development Goal 14, Life Below Water, and encouraged greater ambition and vision by all participants.

The Dialogue resulted in a vision of shared purpose. In a joint statement, CEOs of eight of the world’s largest seafood companies noted that “as keystone actors in the global seafood industry, we recognize that together we represent a global force, not only in the operation of the seafood industry, but also in contributing to a resilient planet with marine ecosystems continuing to produce food of high quality for present and future generations.” Their joint statement set out a long-term vision of transformation, and a specific set of 10 commitments, as well as the formation of a new global initiative: “Seafood Business for Ocean Stewardship” (SeaBOS).

Preparing for a long-term experiment

The establishment of the SeaBOS initiative created new opportunities and responsibilities for the scientists involved. Scientists had led the initial data collection, hypothesis and efforts to convene keystone actors, and to co-develop a statement of science-based action for ocean stewardship. Now, their responsibility would be twofold: to ensure that the keystone companies would be advised of the latest science of relevance for pursuing a vision of ocean stewardship, and to monitor and publicly reflect on the experiment as it continued forward. Would the original hypothesis be realized? Would sustainable leadership by keystone actors result in cascading effects throughout the entire seafood industry and enable a critical transition towards improved management of marine living resources and ecosystems?

The CEOs of SeaBOS member companies also recognized the unique opportunity in the collaboration. The sustainable seafood landscape was already densely populated by initiatives, NGOs and collaborations, but SeaBOS had explicitly defined itself as a unique science-industry collaboration with an ambition and vision that extended beyond the participating companies, to enable cascading positive change across the entire industry. Would this effort be successful? How would its impact be monitored? How could the companies engage with scientists to ensure science-based action, while also enabling the scientists to study all aspects of the collaboration as it unfolded in real time?

The long-term stability of this experiment would rest on several factors:

First, it was imperative that the scientists receive no funding from the companies. The scientists would not work for the companies, but rather alongside, to test the hypothesis and monitor the impacts of the collaboration. Generous funding from the Walton Family Foundation, Packard Foundation, Moore Foundation, the Nippon Foundation and Formas: A Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development, have enabled the science team to maintain independence and focus.

Second, it was crucial to assemble an interdisciplinary team of scientists. Communicating the latest science on ocean stewardship requires interdisciplinary expertise. But understanding how to engage with companies and how to monitor their changes over time also meant building a team with expertise in organizational science, accounting and accountability.

Learn more about the SeaBOS science team

Third, it was vital that the science team publish regularly in open-access peer-reviewed journals on the evolution of the initiative, its efforts to achieve its vision, and the lessons learnt. This meant continuously articulating to the members that the initiative itself was an important study object.

This provided a resource not only to scientists, but also to actors in the private sector and civil society, seeking to learn about the initiative, and where possible to replicate successes, or avoid missteps, as the case may be.

Learn more about the SeaBOS knowledge

A final factor was to some extent beyond the control of the science team: a long-term readiness by members of the SeaBOS initiative to engage in science-industry collaboration. This would depend not only on CEOs, but also on layers of executives and operational staff stepping into areas that would frequently be outside their comfort zone. Here, they would meet scientists – also frequently outside their comfort zone – they would be exposed to new ideas, uncomfortable scrutiny, and difficult conversations. Together, they would co-produce strategies, approaches and initiatives to work towards ocean stewardship. Would reciprocal trust and a shared understanding of the scope and importance of the work enable a long-term collaboration?

Initial analysis

In an initial analysis in 2017, Emergence of a global science-business initiative for ocean stewardship, authors introduced the essential elements of the collaboration to the scientific community for the first time. The paper covered three main topics: (1) the process of identifying the keystone actors in the seafood industry; (2) the process of engaging with these actors and convening the first keystone dialogue; (3) the co-production process that resulted in the establishment of the science-industry collaboration SeaBOS.

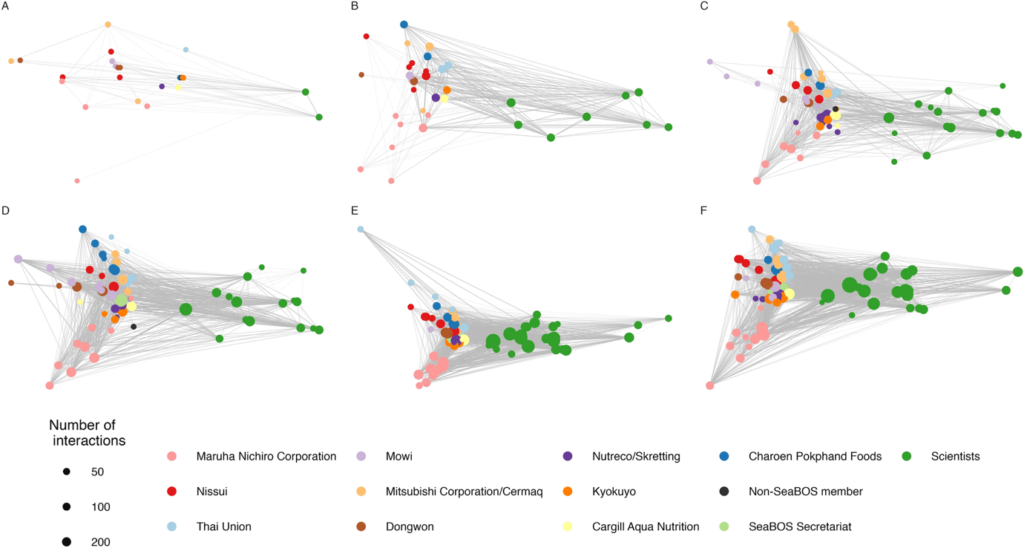

Five years later, in 2022, the SeaBOS initiative had entered a new phase of ambition, accountability and transparency, marked by its first reporting on time-bound goals in its Progress Report, launched at the UN Ocean Conference. Throughout these years, the collaboration was closely studied by the science team, resulting in the peer-reviewed publication Scientific mobilization of keystone actors for biosphere stewardship. Here, the authors described six distinct phases of the collaboration that gradually led to the establishment of a self-funded Secretariat, the articulation of time-bound goals, and tangible results.

Additional key contributions from science team members include Accounting and Accountability in the Anthropocene, an analysis that takes the SeaBOS initiative as a point of reference to explore how the accounting scholarship can evolve to address the nature of environmental and sustainability reporting in the Anthropocene. The long-form article Our Future in the Anthropocene Biosphere explicitly considers the challenges that humanity faces in the Anthropocene, the tools it can use to strive towards transformative change, and provides an in-depth perspective on how SeaBOS exemplifies this new operating context and ambition.

The SeaBOS initiative was also closely studied in the context of knowledge co-production for sustainability, and helped to inform recent foundational publications on the topic: Six Modes of Co-production for Sustainability and Principles for Knowledge Co-production in Sustainability Research. Both publications explore the emerging understanding that sustainability challenges can be most effectively addressed through “co-produced” knowledge that draws on the experience of academics and non-academics.

Finally, the SeaBOS initiative has yielded not only a scientific narrative and an example of novel collaboration, but also a deeply human story. One shaped by relationships, doubts, optimism, worries, fatigue and excitement. This more personal perspective has been captured in a 2023 book, The Sounds of Science: Orchestrating Stewardship in the Seafood Industry.

Inspiring a new and expanding body of research

Science does not exist in a vacuum, but rather relies on reflection, criticism, and diverse perspectives to advance and generate new knowledge. The fact that critical voices have emerged to challenge or critique aspects of the collaboration is a welcome indication that the work is sparking ideas and dialogue.

For instance, the publication Key Challenges to the Corporate Biosphere Stewardship Research Program provides a critique of engagement with corporate actors for co-production. Similar to Making Sense of Firms for Ocean Governance, it suggests that industry concentration is being embraced as an asset for achieving transformational change rather than an inadequately understood and articulated barrier.

These and other themes have been further explored in publications that reflect on the challenges inherent to science-industry collaboration, most notably perhaps in the paper Science-Industry Collaboration: Sideways or Highways to Ocean Sustainability?, which concludes that an “uncritical embrace of science-industry collaboration is unhelpful” and candidly addresses the challenges and opportunities experienced by scientists who have had first-hand experience working in such collaborations. In The Ocean 100: Transnational Corporations in the Ocean Economy, the dominance of the oil and gas sector in the ocean economy is considered, while in Transnational Corporations and the Challenge of Biosphere Stewardship and subsequent correspondence, key empirical questions for a future research agenda are presented, and the importance of government regulations and other incentives to encourage and sanction companies is underscored.

In Evolving Perspectives of Stewardship in the Seafood Industry, authors likewise reflect on the recent history of sustainability efforts within the seafood industry, concluding that despite many positive steps on this path, there is still a tremendous distance to go, as exemplified for instance in the vast room for improvement identified across multiple iterations of the Seafood Stewardship Index of the World Benchmarking Alliance. An additional theme of the paper is that positive developments in the seafood industry have involved multistakeholder collaboration and have rested on a diversity of theories of change, including the recent addition of efforts to engage with keystone actors.

As the academic literature on the keystone actors theory of change matures, the experiment that was set in motion by the 2015 publication will continue to be a foundational piece of the story. Over the years, the SeaBOS initiative has also evolved, expanding from eight to ten members, before contracting to nine members in 2023, while the science team has expanded and diversified its expertise to include a team of 19 individuals at 7 different institutions around the world. On the following pages (The Science Team) and (The Knowledge), it is possible to learn more about the current team of scientists engaging with the SeaBOS initiative, and to access the scientific publications that have been developed in this process.

Early days: An idea takes shape

Early days: An idea takes shape